MORE INFO

- Calling Oregon to Reinvest in Education (CORE)

- Default: The Student Loan Documentary

- Defend Public Education

- Forgive Student Loan Debt!

- Generation Debt

- International Student Movement (ISM)

- Occupy Colleges

- Occupy Everything

- Occupy Student Debt

- Occupy Together

- OccupyPSU

- Oregon Student Association (OSA)

- reclaim UC

- Student Loan Justice

- The DREAM Act

- United States Student Association (USSA)

-

POSTS

ARCHIVED

Next OccupyPSU planning meeting is Monday, Nov. 7th at 2pm

See the calendar for details.

At the last meeting, the coalition decided to adopt an association with the name OccupyPSU. While a physical occupation of Portland State University is not explicitly part of our plans at this time, we feel that the name OccupyPSU embodies the spirit of reclamation we’ve been seeing all over the country lately, whether physical or symbolic.

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Walkout planned for Nov. 16th in solidarity with Occupy movement

Mark your calendars! Wednesday, November 16th, 12pm. More details to come. In the meantime, consider helping out with organizing this event and any future actions it may inspire: come to Terry Shrunk Plaza next Monday, October 31st at 2pm for a planning meeting (meet at PSU in the cafeteria if it’s raining).

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Occupy Colleges

The Nation published this article about student actions in solidarity with the Occupy movement. More to come!

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Oregon Lottery Pays Big, Corporate Tax Not So Much

Check out the article here. It was published back in spring, but is still very relevant. For the 2011-2013 biennium, the Oregon Lottery is projected to pay $1.1 billion to the state, while corporations will only pay $900 million in taxes.

There is a similar trend nationally, according to the same author.

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

$1 Trillion In Loans? How Student Debt Is Killing the Economy and Punishing an Entire Generation

By Sarah Jaffe, AlterNet

Posted on September 21, 2011 (Alternet)

“If you want to take a relation of violent extortion, sheer power, and turn it into something moral, and most of all, make it seem like the victims are to blame, you turn it into a relation of debt.” — Economic anthropologist David Graeber, author of Debt: The First 5,000 Years

Tarah Toney worked two full-time jobs to put herself through college, at McMurry University in Abilene, Texas, and still has $75,000 in debt. She graduated in six years with a Bachelor’s in English and wanted to go on to teach high school.

“Right about the time I graduated, Texas severely cut funding to our education system—thanks, Perry–and school districts across the state stopped hiring and started firing. It became abundantly clear that there was no job for me in the Texas public school system,” she told me. “After two months of job searching I got a temporary position in a real estate office.”

She continued, “In August my post-graduation grace period was up and all of the payments on my student loans amount to $500/month. Adding that expense to my monthly bills puts me at $2,100 per month. If I don’t make my payments they will revoke my real estate license, which I need in order to do my job.”

Max Parker (not his real name) enrolled at Texas A&M in College Station, Texas to get a BA in economics and a BS in physics. His freshman year was great—his parents had saved some money to help pay the bills, and after that he was able to get “more generous” student loans. He took a job to help cover the fees and bills that his student loans wouldn’t cover, and worked about 35 hours a week during his sophomore year while taking 15 hours of classes—but found that his grades dropped with his workload.

“Part of the reason I thought to take on such a heavy load was the university’s newly (at the time) implemented policy of flat-rate tuition,” he explained. “This policy stated basically, no matter how many hours you enroll in (full time) for the semester, you will pay for 15. This means, you enroll in 12 hours or 20 hours, and you’ll pay for 15 hours either way. Being economically minded, I wanted to make the best decisions I could with the money I had been loaned, so I enrolled in 15 hours.”

He adjusted his course load, but in the spring of his junior year, a family emergency led him to withdraw midway through the semester, taking incompletes in his courses.

“I am 25 years old now, and shacking up in my parents’ guest bedroom,” he told me. “I have successfully made four payments on my student loans in the past three and a half years. I have over $48,000 dollars of student loan debt, and absolutely nothing to show for it. No degrees. No certificates. No qualifications. I have continued my education to the best of my ability since leaving A&M, but always at community colleges and always paying for everything out of pocket. As you can imagine, since I’m not ‘qualified’ for a decent paying job, my savings for school piles up very slowly, and then disappears when August and January roll around. I haven’t been back to school in about a year now, and I currently work at Subway, making sandwiches. I don’t make my loan payments.”

He’s about to join the military because he sees it as his only option. “I am depressed at the idea of signing my life away for four years so I can fight someone else’s wars. I am angry beyond belief that it’s come to this,” he said.

Kate Sternwood (not her real name) was recently laid off from a job at a nonprofit organization where she was making $55,000 a year. She has $40,000 in debt from the University of Massachusetts. “When I called my repayment program to tell them I was losing my job, they told me my payment would go from $400 a month to $384 a month because making $55K a year I already qualified for the “hardship” rate.”

The agency in question is Van Ru, a collection agency that takes loans from the Dept. of Education if they go into default. Sternwood said they can’t even tell her what the rate will be when she’s paid enough to get out of default because they don’t know which bank will end up with her loans.

Colleen Williams, a writer in New York, has $975 a month in payments on various student loans from her undergraduate degree at the University of New Mexico and her graduate degree from Parsons School of Design; $325 of that is automatically debited from her account each month after she went into “Student Loan Rehab” after a default.

“When you default on government loans, the collection agency the loans eventually go to are ridiculous,” she said. “Obviously someone defaulting on student loan debt does not have the payoff amount, and they will argue with you, repeatedly, to get you to pay $30,000 off, in full. ‘Don’t you have a friend you can borrow the money from?’ etc.”

Williams noted that she’s not pursuing the career she originally intended after Parsons, which was fashion design. “If I could do it all over again, I would have gone into science,” she said.

Matt Hindman graduated two years ago from Temple University in Philadelphia and is pursuing a career in film. “We are all trying to get our feet wet in our collective industries. The job hunting process costs money too,” he pointed out. “I don’t think it makes sense that I got penalized for being late on payments during my first year out of school. Plus I went into forbearance once, so now my interest is super high from that.”

The story is the same around the country. The economy is stagnant, the job market terrible, and graduates who used to believe their degrees would lead to good jobs are struggling. Meanwhile, the unforgiving student loan system continues to penalize them for their inability to pay.

As Mychal Denzel Smith at the Grio pointed out, “The fundamentals of our economy aren’t strong, but they are the same as ever: we are a country built on low wages and debt.” With those low wages, and particularly with the likelihood of finding a job remaining so low, students who took on debt to pay for an education cannot pay it back. We’re in the middle of another bubble—a student loan bubble. And it doesn’t look like we’ve learned much from the impact the popping of the housing bubble had on our economy—the same lending practices are continuing.

The Bubble

Since the beginning of the recession, most types of credit have gone down. The only exception to that rule has been student loans.

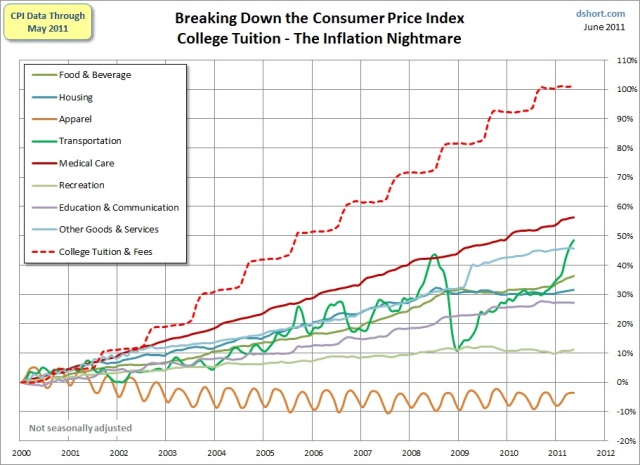

A recent piece in the Atlantic noted that student debt has grown by 511 percent since 1999. At that time, only $90 billion in student loans were outstanding—by the second quarter of 2011, that balance was up to $550 billion, according to the New York Fed. And the Department of Education estimates that outstanding loans total closer to $805 billion—and that number will pass $1 trillion soon.

As student loans rise, so has delinquency. Phil Izzo at the Wall Street Journal reported that 11.2 percent of student loans were more than 90 days past due and that rate was steadily going up. “Only credit cards had a higher rate of delinquency — 12.2 percent — but those numbers have been on a steady decline for the past four quarters,” he noted.

It shouldn’t be surprising to anyone that student loan defaults are going up as young workers especially are struggling in the current economy. Izzo reported, “Workers between 20 and 24 years old have a 14.6 percent unemployment rate, compared to the national average of 9.1 percent recorded in July. That comes even as the share of 20- to 24-year-olds who are working or looking for a job is at the lowest level since the 1970s, before women entered the labor force en masse.”

In his Huffington Post blog, Michigan Democratic Representative Hansen Clarke noted, “This year, the average borrower graduating from a four-year college left school with roughly $24,000 of student debt, despite the grim statistic that — according to a Rutgers University study — only 56 percent of 2010 graduates were able to find work following completion of their studies.”

Back in July, credit rating firm Moody’s Analytics warned that student debt could lead to the next economic crisis. How did student loans go from “good debt” that could be expected to pay off–Pew found that an adult with a bachelor’s degree earns about $650,000 more during their career than a typical high school graduate—to a bubble that threatens the economy?

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, college enrollment skyrocketed 38 percent, from 14.8 million to 20.4 million, between 1999 and 2009. (The previous decade it had only gone up 9 percent.) This should be a good thing—except it was not accompanied by measures to make tuition affordable for working families who wanted to send their kids to school. Combined with the decline in the type of union manufacturing jobs that used to allow workers to be comfortably middle-class without a college degree, we’ve wound up with working-class families taking on debt to send their kids to college, which they are told will help those kids make more money.

Labor economist Mark Price told me:

“Manufacturing was a path into the middle class that didn’t require a college degree but manufacturing has shrunk as a share of all employment and access to similarly high paying good jobs in the service sector typically requires a college education. One other complicating factor is that that the manufacturing that remains in this country often does require more than just a high school diploma for entry.”

As student loans are relatively easy to come by, both from the government and from private lenders increasingly getting into the game, universities have been able to keep hiking tuition without seeing a drop in enrollment. Students are still advised that student debt is “good debt,” as noted above, and that they will be able to pay it off—but the costs are rising far more rapidly than average incomes.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that Temple University has raised tuition every year since 1995—it’s gone up 9.9 percent for in-state students. At the University of Pennsylvania (an Ivy League private university—Temple is the state school) tuition went up 3.9 percent to $42,098 a year. “Throw in a dormitory bed, meals and books, and the price reaches $57,360,” wrote Inquirer reporter Jeff Gammage.

Josh Harkinson at Mother Jones pointed out that like anything else, the bang for your buck isn’t the same at different universities. Private universities have increased per-student spending by about $7,500, he wrote. But public community college spending per student has stayed flat at around $10,000—while those private college students get $36,000 spent on them. He wrote, “It should come as no surprise then that graduates of prestige schools continue to outpace other collegians.”

All of these factors have combined to send student loan debt into the stratosphere. Daniel Indiviglio at the Atlantic pointed out, too, that student debt has far outpaced the growth of all other household debt over the past 10 years—including increasing twice as fast as housing debt. He argued:

“This wasn’t just any average period in history for household debt. This period included the inflation of a housing bubble so gigantic that it caused the financial sector to collapse and led to the worst recession since the Great Depression. But that other debt growth? It’s dwarfed by student loan growth.”

RJ Eskow at the Smirking Chimp noted that the same banks that broke the economy by creating that housing bubble are responsible for the student debt crisis—as well as the federal government, which issues student loans. “[T]hese debts were incurred with broken promises. Much of that money is owed to the government itself, and billions are owed to the banks we bailed out at taxpayer expense,” he wrote.

Student loans are not really comparable to housing loans, though: if you default on your student loans, there’s nothing to repossess. Instead, you’ll face a drop in your credit rating, and constant pressure from the types of collection agencies that Williams and Sternwood discussed above. They can garnish your wages, as Williams explained, and even if you declare bankruptcy, your student loans don’t go away. And as Hindman noted, miss a payment, and your interest rate goes up, creating a punitive spiral of debt there’s no way to escape from.

Even if mass default isn’t likely to happen the same way mortgage defaults did, Indiviglio wrote that the cost of college and debt is already slowing the economy. “As Americans grapple with high student loan payments for the first few decades of their adult lives, they’ll have less money to spend and invest,” he wrote, pointing out that all the money going into colleges and the pockets of lenders in the form of interest is being funneled away from other places it could be spent. “Of course, this would be a rather unfortunate irony: higher education is supposed to enhance a nation’s growth, but with such an enormous debt burden, graduates might not be able to spend and invest enough to allow that growth to occur.”

Iris Van Kerckhove, who blogs about business at On My Grind, wrote:

“Now the labor pool is flooded with people who have postgraduate degrees and are desperate for work. Employers are overwhelmed with the number of applicants and, in response, demand higher qualifications as a way to filter the applications. Yet higher education institutions continue selling something that doesn’t exist– a guarantee of a better future. Something’s gotta give.”

The Solutions

So what can give?

Mychal Smith reminded us that just last year in his State of the Union, President Obama proclaimed, “No one should go broke because they chose to go to college.” He called for student loans to be forgiven after 20 years—10 for those who go into public service—and a $10,000 tax credit for families paying for a four-year college.

But that’s not a solution for people like Parker, who was unable to finish school because of the cost, or Toney, who wanted to go into public service but saw that door shut in her face with state budget cuts. They’re in debt now, not in 20 years, and $10,000 doesn’t begin to cover their debt, let alone the $80,000 Williams owes for a graduate degree. As tuition goes up thousands of dollars a year, a $10,000 tax credit looks pretty measly—and the chances of getting even that through the current Congress are slim to none.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that New Jersey’s state legislature has a bill under consideration that would ban state colleges from raising tuition more than 2 percent a year. Keeping tuition down is certainly part of the solution—tuition growing faster than wages is a recipe for defaults as students struggle to pay back their loans. In addition, just as housing prices going way up wound up pricing many people out of home-buying, increases in tuition will price students out of an education—particularly if the benefits of that education become less clear, as jobs remain hard to come by.

One university actually lowered its prices recently. The Inquirer reported that Sewanee, the University of the South, a private school in Tennessee, cut its annual cost 10 percent, from about $46,110 to $41,000–without closing programs or laying off staff:

“Enrollment was better than expected, alumni giving went up, and some parents donated the $5,000 price difference back to the university. The deficit turned out to be half of what was projected, at $1.5 million, and Sewanee got the bump in publicity it sought: Campus visits increased 60 percent.”

But what do we do for the people who’ve already finished college but are stuck without jobs and with mounting debts? RJ Eskow proposed a “Youth WPA,” imitating the Works Progress Administration from the New Deal to put young people to work rebuilding our infrastructure, developing new business ideas, make creative works that we can all enjoy, and more (his six-part proposal is worth reading in detail).

An idea that’s been getting a lot of traction lately—including an online petition pushed by MoveOn member Robert Applebaum that has 320,000 signatures as of this writing—is student loan forgiveness as economic stimulus.

Rep. Hansen Clarke introduced a resolution in Congress, co-sponsored by 12 other members, that includes student loan forgiveness in its suggestions for bringing down the U.S.’s “true debt burden.”

In his Huffington Post blog, Clarke wrote:

“Congress is now completely focused on reducing debt. This would be a positive development, if not for one detail: it’s focused on the wrong kind of debt.

With over a quarter of all American homeowners “underwater” — owing more on their homes than their homes are worth — and total student loans slated to exceed $1 trillion this year, it is household debt, not government debt, that is constraining spending, undermining confidence, and precluding sustainable long-term growth.”

Clarke is right. For years, credit was a substitute for real wage growth in the U.S. And now as that debt burden has grown unsustainable, working families are barely able to keep up with payments, let alone spend enough to get the economy back on its feet. And student debt, as we’ve shown, is on the least sustainable trajectory of all.

Mychal Smith wrote:

“[C]onsider the potential impact on the economy if all of a sudden 35 million people were able to add to their monthly budget anywhere between $400 and $1000 that they no longer needed to satisfy exorbitant student loan repayments. And no longer faced with the threat of default(at a rate of 7 percent as of September 2010), credit scores would rise and more people with inclination toward starting small businesses (those things that every politician proclaims drive economic growth)[could do so]. Debt free degree holders would allow for more risk taking and innovation.”

Student debt forgiveness would put $400 a month back into Sternwood’s pockets, $975 a month in Williams’. Even just forgiving the government loans would probably allow Parker to finish his degree instead of going to war.

Of course the resolution is unlikely to pass Speaker John Boehner’s Congress, and even if it does, it’s just a resolution. But the instant popularity of Applebaum’s petition shows something: Americans realize that student debt at the current levels is completely untenable, and something must be done soon.

Republicans love to talk about the debt we’re leaving our children with. But saddling them with record levels of student debt and no jobs with which to earn money to pay it back hurts young people much, much more than government budget deficits.

Sarah Jaffe is an associate editor at AlterNet, a rabblerouser and frequent Twitterer. You can follow her at @seasonothebitch.

© 2011 Independent Media Institute. All rights reserved.

View this story online at: http://www.alternet.org/story/152477/

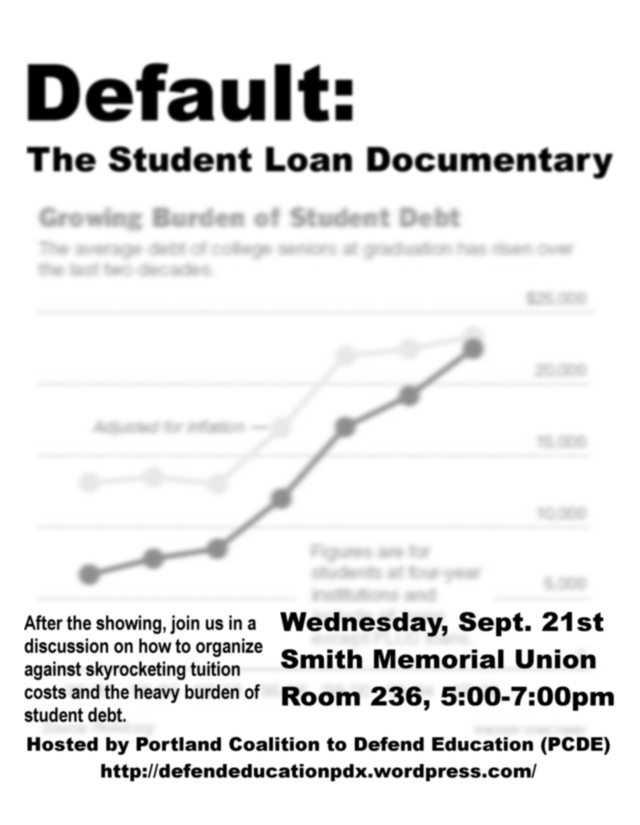

PCDE is showing “Default” for New Student Week

The Portland Coalition to Defend Education will be hosting a showing of “Default: The Student Loan Documentary” for Portland State’s New Student Week. The documentary will be shown on Wednesday, September 21st at 5pm in Room 236 of Smith Memorial Union. A discussion on organizing against increasing tuition costs and student debt will be facilitated after the showing. All are welcome.

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Chomsky: Public Education Under Massive Corporate Assault — What’s Next?

Converting schools and universities into facilities that produce commodities for the job market, privatizing them, slashing their budgets — do we really want this future?

August 5, 2011 |

The following is a partial transcript of a recent speech delivered by Noam Chomsky at the University of Toronto at Scarborough on the rapid privatization process of public higher education in the United States.

A couple of months ago, I went to Mexico to give talks at the National University in Mexico, UNAM. It’s quite an impressive university — hundreds of thousands of students, high-quality and engaged students, excellent faculty. It’s free. And the city — Mexico City — actually, the government ten years ago did try to add a little tuition, but there was a national student strike, and the government backed off. And, in fact, there’s still an administrative building on campus that is still occupied by students and used as a center for activism throughout the city. There’s also, in the city itself, another university, which is not only free but has open admissions. It has compensatory options for those who need them. I was there, too; it’s also quite an impressive level, students, faculty, and so on. That’s Mexico, a poor country.

Right after that I happened to go to California, maybe the richest place in the world. I was giving talks at the universities there. In California, the main universities — Berkeley and UCLA — they’re essentially Ivy League private universities — colossal tuition, tens of thousands of dollars, huge endowment. General assumption is they are pretty soon going to be privatized, and the rest of the system will be, which was a very good system — best public system in the world — that’s probably going to be reduced to technical training or something like that. The privatization, of course, means privatization for the rich [and a] lower level of mostly technical training for the rest. And that is happening across the country. Next year, for the first time ever, the California system, which was a really great system, best anywhere, is getting more funding from tuition than from the state of California. And that is happening across the country. In most states, tuition covers more than half of the college budget. It’s also most of the public research universities. Pretty soon only the community colleges — you know, the lowest level of the system — will be state-financed in any serious sense. And even they’re under attack. And analysts generally agree, I’m quoting, “The era of affordable four-year public universities heavily subsidized by the state may be over.”

Now that’s one important way to implement the policy of indoctrination of the young. People who are in a debt trap have very few options. Now that is true of social control generally; that is also a regular feature of international policy — those of you who study the IMF and the World Bank and others are well aware. As the Mexico-California example illustrates, the reasons for conscious destruction of the greatest public education system in the world are not economic. Economist Doug Henwood points out that it would be quite easy to make higher education completely free. In the U.S., it accounts for less than 2 percent of gross domestic product. The personal share of about 1 percent of gross domestic product is a third of the income of the richest 10,000 households. That’s the same as three months of Pentagon spending. It’s less than four months of wasted administrative costs of the privatized healthcare system, which is an international scandal.

It’s about twice the per capita cost of comparable countries, has some of the worst outcomes, and in fact it’s the basis for the famous deficit. If the U.S. had the same kind of healthcare system as other industrial countries, not only would there be no deficit, but there would be a surplus. However, to introduce these facts into an electoral campaign would be suicidally insane, Henwood points out. Now he’s correct. In a democracy where elections are essentially bought by concentrations of private capital, it doesn’t matter what the public wants. The public has actually been in favor of that for a long of time, but they are irrelevant in a properly run democracy.

We should recall that the great growth period in the economy — the U.S. economy — was in the several decades after WWII, commonly called the “Golden Age” by economists. It was substantially fueled by affordable public education and by university research. Affordable public education includes the GI Bill, which provided free education for veterans — and remember, that was a much poorer country than today. Extremely low tuition was found even at private colleges. Actually, I went to an Ivy League college, and it cost $100 a year; that’s more now, but it’s not that high, it’s not 30 or 40,000, you know?

What about university-based research? Well, as I mentioned, that is the core of the modern high-tech economy. That includes computers, the Internet — in fact, the whole IT revolution — and a whole lot more. The dismantling of this system since the 1970s is among the many moves toward a very sharply two-tiered society, a very narrow concentration of wealth and stagnation for most everyone else. It also has direct economic consequences. Take, say, California. What they are doing to the public education system is going to undermine the economy that relies on a skilled work force and creative innovation, Silicon Valley and so on. Well, apart from the enormous human cost of depriving most people of decent educational opportunities, these policies undermine the U.S. competitive capacity. That’s very harmful to the mass of the population, but it doesn’t matter to the tiny percent of concentrated wealth and power. In fact, in the years since the Pell Memorandum, we’ve entered into a new stage in state capitalism in which the future just doesn’t amount to much. Profit comes increasingly from financial manipulations. The corporate policies are geared toward the short-term profit, and that reduces the concern for loyalty to a firm over a longer stretch. We’ll talk about this more tomorrow, but right now let me talk about the consequences for education, which are quite significant.

Suppose, as is increasingly happening not only in the United States, incidentally, that universities are not funded by the state, meaning the general community. So how are the universities going to survive? Universities are parasitic institutions; they don’t produce commodities for profit, thankfully. They may one of these days. The funding issue raises many troubling questions, which would not arise if fostering independent thought and inquiry were regarded as a public good, having intrinsic value. That’s the traditional ideal of the universities, although there are major efforts to change that. Take Britain. According to the British press, the Arts and Humanities Research Council was just ordered to spend a significant amount of funding on the prime minister’s vision for the country. His so-called “Big Society,” which means big corporate profits, and the rest look out for themselves. The government produced what they call a clarification of the famous Haldane Principle. That’s the century-old principle that barred such government intrusion into academic research. If this stands, which I think is kind of hard to believe, but if it stands, the hand of Big Brother will rest quite heavily on inquiry and innovation in the arts and humanities as the masters of mankind follow the advice of the Pell Memorandum. Of course, defending academic freedom in ways that would receive nods of approval from Those-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named, borrowing my grandchildren’s rhetoric. Cameron’s Britain is seeking to take the lead on the assault on public education. The rest of the Western world is not very far behind. In some ways the U.S. is ahead.

More generally, in a corporate-run culture, the traditional ideal of free and independent thought may be given lip service, but other values tend to rank higher. Defending authentic institutional freedom is no small task. However, it is not hopeless by any means. I’ll talk about the case I know best, at my own university. It is a very striking case, because of the nature of its funding. Technically, it’s a private university, but it has vast state funding, overwhelming, particularly since the Second World War. When I adjoined the faculty over 55 years ago, there were military labs. Since then, they’ve been technically severed. The academic programs, too, at that time, the 1950s, were almost entirely funded by the Pentagon. Under student pressure in the time of troubles, the 1960s, there were protests about this and calls for investigation. A faculty-student commission was formed in 1969 to investigate the matter. I was a member, thanks to student pressure. The commission was interesting. It found that despite the funding source, the Pentagon, almost the entire academic program, there was no military-related work on campus, except in the sense that virtually anything can have some military application. Actually, there was an exception to this, the political science department, [which] was deeply engaged in the Vietnam War under the guise of peace research. Since that time, Pentagon funding has been declining, and funding from health-related state institutions — National Institute of Health and so on — that’s been increasing. There’s a reason for that. It’s reflecting changes in the economy.

In the 1950s and 1960s the cutting edge of the economy was electronics-based. The Pentagon was a natural way to steal money from the taxpayers, making them think they’re being protected from the Russians or somebody, and to direct it to eventual corporate profits. That was done very effectively. It includes computers, the Internet, the IT revolution. In fact most of the modern economy comes from that. In more recent years, the economy is becoming more biology based. Therefore state funding is shifting. Fifty years ago, if you looked around MIT, you found small electronics startups from the faculty. They were drawing on Pentagon funding for research, and if they were successful, they were bought up by major corporations. Those of you who know something about the high-tech economy will know that that’s the famous Route 128. That was 50 years ago. Now, if you go around the campus, the startups are biology based, and the same process continues. The genetic engineering, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals and the big buildings going up are Novartis and so on. That’s the way the so-called free enterprise economy works. There’s also been a shift to more short-term applied work. The Pentagon and the National Institutes of Health are concerned with the long-term future of the advanced economy. In contrast to a business firm, it typically wants something that it can use — it can use and not its competitors, and tomorrow. I don’t actually know of a careful study, but it seems pretty clear that the shift toward corporate funding is leading towards more short-term applied research and less exploration of what might turn out to be interesting and important down the road.

Another consequence of corporate funding is more secrecy. This surprises a lot of people, but during the period of Pentagon funding, there was no secrecy. There was also no security on campus. You may remember this. You walk into the Pentagon-funded labs 24 hours a day, and no cards to stick into things and so on. No secrecy; it was all entirely open. There is secrecy today. A corporation can’t compel secrecy, but they can make it very clear that you’re not going to get your contract renewed if your work leaks to others. That has happened. In fact, it’s lead to some scandals, some big enough to appear on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.

Outside funding has other effects on the university, unless it’s free and unconstrained, observing the Haldane Principle. Indeed, it has been true to a significant degree by funding from the Pentagon and the other national institutions. However, any kind of outside funding [has effects], even keeping to the Haldane Principle, supposing it establishes a teaching or research facility. That kind of automatically shifts the balance of academic activity, and that can threaten the independence and integrity of the institution. And in the case of corporate funding, quite severely.

Corporatization can have considerable influence in other ways. Corporate managers have a duty. They have to focus on profit making and seeking to convert as much of life as possible into commodities. It’s not because they’re bad people; it’s their task. Under Anglo-American law, it’s their legal obligation as well. There’s a lot to say about this topic, but one element of it concerns the universities and much else. One particular consequence is the focus on what’s called efficiency. It’s an interesting concept. It’s not strictly an economic concept. It has crucial ideological dimensions. If a business reduces personnel, it might become more efficient by standard measures with lower costs. Typically, that shifts the burden to the public, a very familiar phenomenon we see all the time. Costs to the public are not counted, and they’re colossal. That’s a choice that’s not based on economic theory. That’s based on an ideological decision, which applies directly to the “business models,” as they’re called, of the universities. Increasing class-size or employing cheap temporary labor, say graduate students instead of full-time faculty, may look good on a university budget, but there are significant costs. They’re transferred and not measured. They’re transferred to students and to the society generally as the quality of education, the quality of instruction is lowered.

There’s, furthermore, no way to measure the human and social costs of converting schools and universities into facilities that produce commodities for the job market, abandoning the traditional ideal of the universities. Creating creative and independent thought and inquiry, challenging perceived beliefs, exploring new horizons and forgetting external constraints. That’s an ideal that’s no doubt been flawed in practice, but to the extent that it’s realized is a good measure of the level of civilization achieved.

That idea is being challenged very openly by Adam Smith’s Principal Architects of Policy in the State Corporate Complex, the direct attack on the Haldane Principle in Britain. That’s an extreme case; in fact so extreme I assume it may be beaten back. There are less blatant examples. Many of them are just inherent in the reliance on outside funding, state or private. These are two sources that are not easy to distinguish given the control of the state by private interest. So what’s the right reaction to outside funding that threatens the ideal of a free university? Well one choice is just to reject it in principle, in which case the university would go down the tubes. It’s a parasitic institution. Another choice is just to recognize it as a fact of life that when I’m at work, I have to walk past the Lockheed Martin Lecture Hall, and I have to look out my office window at the Koch building, which is named after the multibillionaires who are the major funders of the Tea Party and a leading force in ongoing campaigns to wipe out the remnants of the labor movement and to institute a kind-of corporate tyranny.

Now, if that outside funding seeks to [influence] teaching, research and other activities, then there’s a strong argument that it should simply be resisted or rejected outright no matter what the costs. Such influences are not inevitable, and that’s worth bearing in mind.

Read more of Noam Chomsky’s work at Chomsky.info.

Annnnnd…. we’re back!

After a long while of no activity on this site, PCDE is readopting our online presence. Check back soon for more updates!

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Ending the Assault on Public Education

Ending the Assault on Public Education

In solidarity with a nation wide movement, students at Portland State University and residents of the state of Oregon find it imperative to raise awareness with the general public about the current trends relating to local and national public education. For the past two decades in particular public funding for education has continually decreased. In part, this is due to the fact that the Oregon legislature decides upon policy and tax expenditure every two years, keeping the beneficiaries, the people, in a lag between the time that economic factors affect them and to when they may receive the required funding for assistance.

The value of public education in the eyes of the average American has also faced a downturn. The turn towards private schools for those who can afford them further deteriorates the notion of education as a public good. People find every approach to funding and policy, whether endorsed by our political left or right, to blame for the failures of our education system. As much faith as we have (or lack) in the method which our system operates, the future of the people of Oregon relies on the quality that our public education institutions are able to provide them with. Given these complex issues, an outcome that would benefit those seeking to receive an education is not impossible, yet not easy.

A number of critiques concerning education are as follows:

- Centralizing the source of funding for public education to private and corporate interest groups is synonymous to self strangulation. Our hope is to keep education accessible to all, which requires that a broad curriculum be available, not a channeled prospectus set by business contracts by private interest groups.

- The State of Oregon’s planning capabilities that are oriented toward caring for its people is shallow due to the construction of the state budget, mainly the General Fund, which allocates money to services that provide supply to the demand of the people. This promotes competition between services that are meant to benefit the people of Oregon, you and I.

- Continual war spending has drained our national economy. The residents of Oregon face continual siphoning of their hard earned income in the form of taxation, funneling funds away from needed public services to instead fuel military operations that have largely failed concise military objectives.

- A tuition increase that passed the 100% mark in a number of decades, compared to the per capita income of Oregon residents, indicates a misplaced sense of duty that policymakers execute, placing their interests on profit instead of people.

- Oregon has the fifth highest rate of unemployment nationwide, as of August, 2010, standing at 10.6% according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Graduates of universities are finding it increasingly difficult to find jobs with such dismal employment prospects.

These problems may be seen as overwhelming, even intimidating. Yet there is no indication that solutions are non-existent. The communities of Oregon must understand the long-term and short-term implication how the deterioration of public education affects all of us. Any well educated economist will tell you that the best solution to a recession is an educated public. The lessons that history teach us tend to indicated the errors of human ways. Rather than concentrate on the historical errors committed, we hope to encourage the involvement of all of Oregon in finding the solution to this problem and the surrounding factors that influence it so.

On October 7th 2010 a coalition of student groups, having responded to a national call to action, will be holding an event that is dedicated to these very problems. It would be our modest hope, if what you find in the news media of today to be troubling, to take the time to hear, learn and organize with the intent to change the future we all have to live with. Come to the South Park Blocks at Portland State University on October 7th, from 10 am to 2 pm to be part of this.

For further information, email pcde@googlegroups.com

This message is brought to you by the Portland Coalition to Defend Education.

Posted in Uncategorized

1 Comment